This is the fourth and final step in my FOREfront method series. You can catch the overview here, first step here, the second step here, and the third step here.

Well, here we are, the final step of my FOREfront method. This step is called “Embed” and it may be the most important of all because if you don’t embed desired practices, there’s no point teaching them in the first place. Running a one-day workshop might mean you can put a check next to “training” on your list, but without backing it up, you’ve just washed time and money down the drain.

With that in mind, in this article, I’m going to demonstrate:

- Why it’s not enough to learn something once; training needs to be repeated to embed desirable behaviours.

- Why repeated practice actually saves you money.

Alright, game plan done, let’s go.

Why one-and-done is never enough

Contrary to the Department of Education’s opinion, studying something in one big block with a test at the end and never revisiting that content again does not lead to good learning results. Rather, the attainment of knowledge and understanding requires repeated practice, over time.

Get your glasses out, I'm going to prove that statement using science.

The forgetting curve and spaced repetition

In the learning community, we’re obsessed with a principle called “spaced repetition”. Simply put, spaced repetition is presenting the same content at spaced intervals. It also goes by the name "revision". The need for spaced repetition is innate: we all know that cramming doesn't lead to long-term retention. You might pass the test the next day, but the information quickly falls out of your head. Quickly forgotten, hardly remembered.

However, the forgetting phenomenon is scientifically backed and was plotted on a curve way back in 1885, by a man called Hermann Ebbinghaus.

Ebbinghaus was a German psychologist who conducted a series of experiments where he would write down a bunch of random syllables like this:

XBH, AOJ, APK, AJI, AOI

He would then repeat them to himself until he had them completely memorised. Once he had them down pat, he would attempt to recall that series of syllables at periodic intervals; after a day, after two, then a week, a month, even six weeks after first learning them. After each attempted recall, he recorded exactly how many of the syllables he could summon in the correct order, and plotted them on a graph. That graph looked something like this:

His findings definitively determined what we already know: our brains are leaky buckets. If, at the time of first learning something you know 100% of that content, a day later you'll only know about 50% of that same content. A month after learning something, you’re at around 80% retention. That percentage continues to get less and less until soon enough, you remember hardly anything of that content at all.

However, Ebbinghaus also proved another thing we already know: the way to counteract this is through revision. If you revise something a day, a week, even a month after you first learn it, it strengthens the memory in your mind, and makes the forgetting curve much more gradual. It starts looking more like this:

Science meets FOREfront

In my earlier FOREfront articles, I talk about how critical customer service frameworks and role-playing are to creating a customer service experience so good that customers rave about you to anyone and everyone they know. The missing element of frameworks and role-playing is, however, embedding what you learn.

Good customer service is natural, easy. It doesn’t feel like a performance, like someone is rattling off key phrases or acting how they’ve been told to act. Customer service, really, is the art of being likeable. And we all know those really ‘likeable’ people, they’re natural. Nothing seems rehearsed, or as though they’re trying at all.

While we think of likability as something innate to a person’s personality, it is actually something that can be practiced and perfected. Think of celebrity talk-show interviews - we all love the celebrities that have been in the game for years: Tom Hanks, Betty White, Elmo. They talk, it’s natural, we love them. While of course, some people are naturally more charismatic than others, the reason these people come across as so likeable is because they’ve had years of practice; talk show after talk show, interview upon interview. All that practice can make any learned behaviour appear innate.

The same is true for customer service. Some people are just “people” people. But no matter how much of a people person you are, you still need practice. To learn how to relate to others, to react to requests, and make it all seem effortless and smooth. Practice makes perfect, yes, but it does more than that: practice makes natural. Practice is how concert pianists can make playing Beethoven seem like a natural, simple act.

That’s why it’s not enough to do your roleplaying session or go over your customer service frameworks only once. No, to create customer service excellence we need to be continuously learning and repeating our practices, so that the behaviours they’re designed to elicit are embedded and form part of our natural behaviours.

But what about the money, Mark??

I know what you’re thinking, ‘That’s great, Mark. I know repetition is ideal but I can hardly find the time and money to train everybody once, let alone multiple times.’ To which I say, with all due respect, I disagree. In fact, if you’re worried about money then you definitely need to be repeating and embedding your training.

The argument in favour of embedding training through repeated practice is a financial one: corporate training is a stranded asset if the content taught is not retained - you can’t get any ROI from skills you can’t remember how to do. Therefore, it’s financially unsound not to embed training. Further, through focusing on what people really need to know, and being considered in how and when you deliver that content, it shouldn’t take hours to repeat practice. Or, in other words: embedded practice gets you more bang for your buck, aka helping justify to the CFO that you are driving ROI from your learning budget.

Saving money by honing in on the need-to-know points

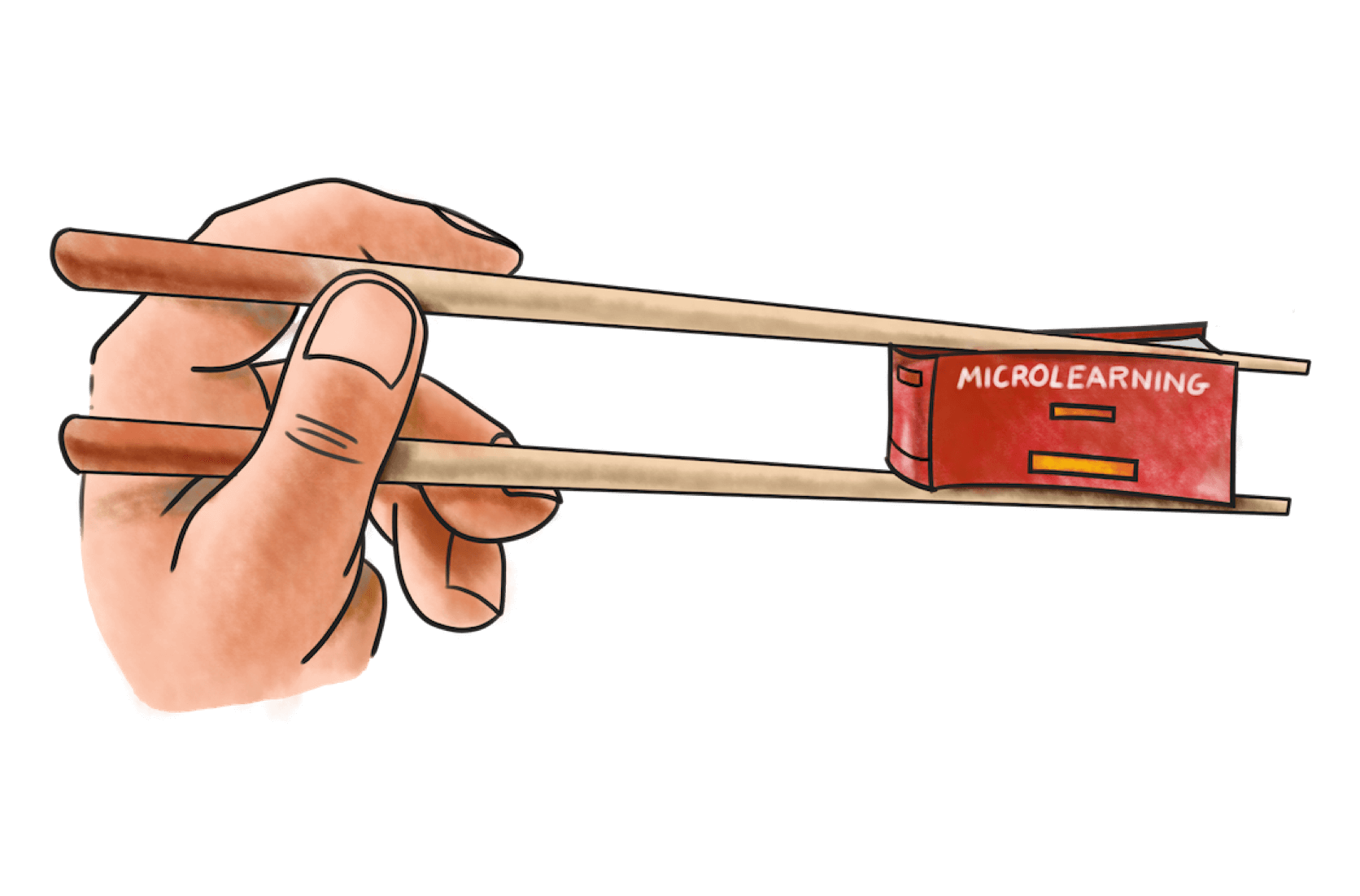

The reason why a lot of us don't revise isn't because we don't want to learn, but because we simply don't have the time to go through mountains of content once, let alone two or three times. But if you don’t have a mountain of content to go through, then it’s easy to repeatedly practice it.

That’s why, while I’m a big advocate for training and learning, I’m not an advocate for unnecessary training and learning. Seneca the Younger wrote that the pursuit of superfluous knowledge, ‘makes men troublesome, wordy, tactless, self-satisfied bores, who fail to learn the essentials just because they have learned the non-essentials.’

I must be a philosopher because I also think learning unnecessary knowledge is a waste of time and only serves to give the appearance of learning without any material benefit. Which is why, rather than trying to know everything, we need to separate the wheat from the chaff. The job of training isn't to provide an encyclopaedic inventory of everything to do with a particular topic, but to effectively teach the need-to-know points within a particular topic.

So, let’s two-birds-one-stone it. Before rushing in to training, first step back and answer the question, ‘What do people really need to know?’ Once you’ve answered that question, build your course around that key material, and learn that and learn it again. Learn it so much it’s embedded in who you and you don’t know where you end and wisdom begins. A short, but effective and repeated course beats an unwieldy, un-repeated course every time.

What it’s all for

We’re all here because of the customer. Without them, we’ve got nothing, which means that their interests are our interests. I created the FOREfront method because a lifetime of working in customer-facing roles has shown me that customer-service is about building relationships. The trick is really caring; about the customer, about each interaction, about ensuring every service rendered is as good as the last one. And the trick to doing all that is as simple as it gets: practice.

Practice until everything you’ve learnt comes naturally, until it’s embedded in your behaviours. And once you do, you’ll find that just like we all rave about how nice Tom Hanks seems, customers will rave about how great your service is, to anyone and everyone they can find.

To learn about the big impact little bites of learning can have, download our microlearning white-paper.